I first encountered the work of Maïmouna Guerresi about a year ago at an art fair in Italy, thanks to a colleague who put us in touch. A few months later, I took the train to visit the artist in her home- studio in Monteforte, near Verona.

Maïmouna greeted me at the station in her Volvo and welcomed me into her space of work, production, and collection—a place where the artworks she has created over the years coexist with those that have traveled across continents for exhibitions.

Among crates and stored works, I was able to see her early photographic and sculptural pieces from the 1970s, when she was still known as Patrizia Guerresi. At that time, her reflection stemmed from the relationship between body and nature, exploring how the two elements merge and transform one another.

Maïmouna then showed me the sculptures she has created over the years in metal and other materials, her production of monotypes—or “pressures,” as she calls them—on paper, textile tapestries, and the series made after 1991, when she embraced Islam and joined the Murid Sufi order.

In one map-tapestry, her two countries are stitched one within the other: the borders of Senegal are sewn in proportion, and inside it—like a small heart—is the Veneto region, her place of origin in northeastern Italy. Her homes and family are in both Senegal and Italy, and she holds dual citizenship.

Along the outer perimeter of her Monteforte house, I noticed a wall that had clearly been painted over many times. It serves as the backdrop for the murals the artist creates each time she photographs or films, changing its color to complete the composition she is working on. She explains that there is a twin wall in her family home in Dakar.

Inside, there is a white-walled studio that has served as the set for many of her works, where I recognize the window that provides the light source for several of her images.

Drawing on my background in art history in Italy, I could trace in Guerresi’s works certain symbols reminiscent of Christian iconography—particularly those from Tuscan Renaissance painting. But Maïmouna directs me instead toward a new visual horizon: one that embraces syncretism, connects archetypes with new figuration, and establishes the centrality of the female, Black, and Muslim figure.

The characters depicted in her photographic series may become “Giantesses”: vertically elongated, draped in cloaks, and compact like statues. They exist outside of any specific time or space, as the background color is flat and uniform, without a landscape to define a setting. It evokes instead an immaterial world governed by equilibrium and harmony—suspended between the present and a future that absorbs the past within itself.

Maïmouna elevates young Black women to the role of protagonists: a deliberate choice that overturns Eurocentric and colonial perspectives, which have systematically excluded Black African bodies and erased their histories.

The Martinican anthropologist Frantz Fanon (1925–61), in his 1952 book Black Skin, White Masks, wrote that assimilating the colonizer’s language creates a rupture with the consciousness of one’s original culture and with one’s Black body. The misunderstanding and solitude that arise from this clash of codes were explored by Senegalese writer and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène (1923–2007).

Self-taught, Sembène began making films at the age of forty; in 1963 he directed the memorable black-and-white film La noire de…, whose protagonists are often Black women. In a famous interview, Sembène declared that he did not make films for Europeans—and in a similar way, Guerresi moves within an artistic space that seeks to transcend geographical and cultural boundaries. It is for this reason that her work finds resonance and success across continents.

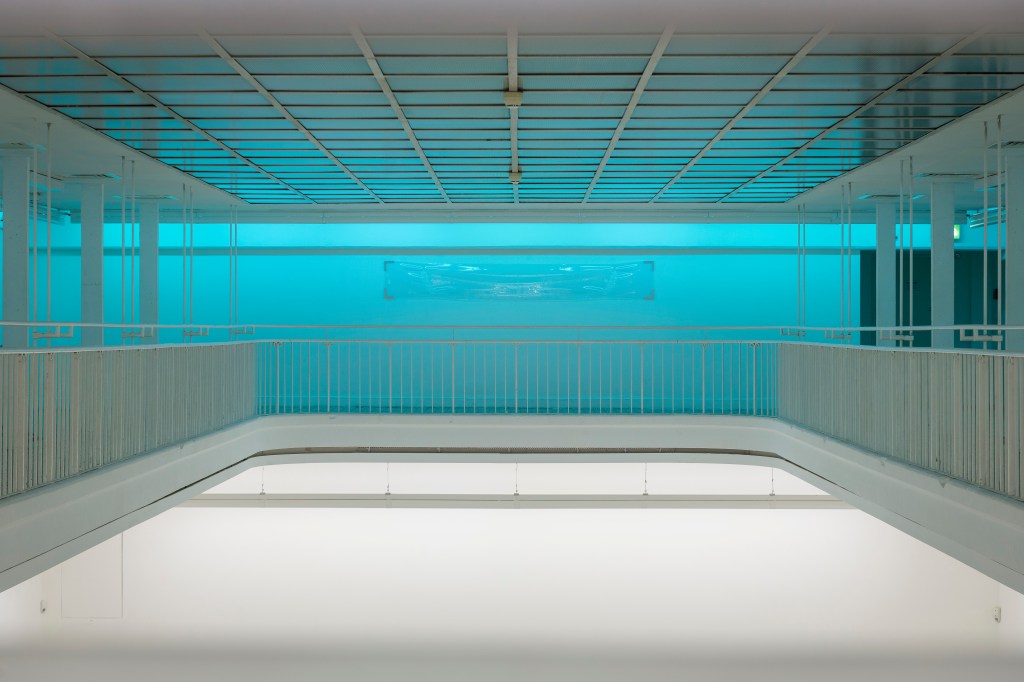

Madrasat ‘Athina, the project by Maïmouna Guerresi created for the Italian Cultural Institute of Dakar, brings to Senegal a visual reinterpretation of Raphael Sanzio’s fresco The School of Athens, in which some of the greatest thinkers of Greco-Roman antiquity are depicted in the Vatican Rooms in Rome.

At the center of the painted architectural perspective, Raphael portrays the philosophers Plato and Aristotle, symbolizing the pinnacle of Renaissance thought that placed humankind at its center.

From this compact group of philosophers, Guerresi brings forth a woman: the mathematician Hypatia. Although this theory is not widely supported by scholars, one hypothesis suggests that the detached figure gazing toward the viewer could be Hypatia of Alexandria, in Egypt. Living between the 4th and 5th centuries CE, she was the first woman known—through documentation—to have taught mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy to a large following, before being murdered for standing in the way of Bishop Cyril’s growing power.

In both works—the Vatican fresco by Sanzio and Guerresi’s installation in Dakar—the protagonist’s face turns toward the viewer, one hand resting on her right shoulder, grasping the drapery, while the other holds a circle open-palmed—perhaps a celestial wheel—in a harmonious mystical representation.

The Madrasa of Athens thus proposes a school of women, subverting what is seen in The School of Athens. Here, two female philosophers mirror the gestures of Plato and Aristotle from the Vatican fresco, beneath a pointed arch typical of Islamic architecture. Around them, several students (ṭālibī) applaud, as if celebrating a new center of knowledge.

The large photograph Alif Lam Mim shows three women reading, with a small girl crouched between them pointing to the symbol Alif Lam Mim, replacing the motif of the original fresco.

The circle is marked by a large compass held by a woman on a table, while three other female figures observe attentively. A recurring element is the small golden sphere—an allegory of the search for knowledge. In another scene, a boy plays with the same sphere, which here becomes a symbol of a fragile yet precious science.

In the video La Création du Monde, Guerresi presents an aerial dance of what at first appear to be black clouds, but on closer inspection turn out to be plastic bags. The soundtrack features the voice of Senegalese cultural figure n’Gonè Fall, reciting in Wolof the creation story according to an ancient Dogon oral tale from Mali.

In this poetic reinterpretation, Maïmouna also refers to Senegalese anthropologist Cheikh Anta Diop (1923–1986), the first to assert that the ancient Egyptian language marked the cultural beginning of Black Africa and formed the foundation of Mediterranean civilizations, which in turn influenced Greek and Roman philosophers.

The symbolic objects recurring in Guerresi’s work remind us of contemporary issues that severely affect the African continent: plastic and gasoline as symbols of the energy crisis and pollution. Yet there are also important references to nature and to Islam—the great baobab tree, the white of milk, the red of blood. Maïmouna constantly draws inspiration from the mystical figures of Muslim Africa, affirming:

“[…] the metamorphosis of my spirit is reflected in my works. My symbolic representation of the Black body becomes an extension of myself.”

(from an email exchange between the artist and the author).

In one image on view, a young girl presents to the viewer a black board inscribed in Arabic calligraphy with Alif Lam Mim—a formula repeated many times in the Qur’an. In this way, the work invites us to open ourselves to further interpretations and pathways of meaning.

In Maïmouna Guerresi’s artistic practice, making worlds, as the French philosopher Séverine Kodjo-Grandvaux teaches us, means connecting knowledge and wisdom beyond any kind of barrier—without one position dominating the other—but rather in a vibrant and harmonious coexistence.

Caterina Riva, 2025 for Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Dakar, Senegal